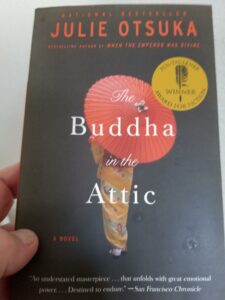

The Buddha in the Attic reads like a meditation. Like a chant. Like a chronicle of the collective lives of the many Japanese women who emigrated as mail order brides to California in the 1900’s to marry Japanese men already landed in the U.S.

It’s not a novel as I’ve come to understand novels. Yet it does weave a story. It focuses on the collective lives of these women through their voyage, their nuptials to men they do not know, their loving and unloving marriages, their childbearing, the prejudice they receive, they prejudices they dole out, and their eventual forced evacuations from the lives they have built to internment camps at the onset of WWII.

The Buddha in the Attic tells of the women’s arrival and eventual disappearance from the Western American landscape.

The book is told through a mix of both first-person singular and first-person plural narration. We hear of one woman’s hardship or a collectively shared joy. The story builds not as a personal central character’s story of triumph or defeat, but as a connective weave of small anecdotes, observations, and disappointments that makes this universal saga intimate.

What carries the story is its rhythm. The Budda in the Attic is written as a chanted meditation. The words and phrasing repeat throughout the paragraph and the paragraph style repeats throughout the book, absorbing the reader into both the words’ meaning and ambience. In this way Otsuka brings us close while leaving us a distance. In observing the travails of the women we connect their lives with our own, seeing ourselves in them.

Consider how in the following passage Otsuka uses repetition and rhythm to guide us through a small peek into how easily they are dismissed that flows in a bigger saga of the roles they play.

They gave us new names. They called us Helen and Lily. They called us Margaret. They called us Pearl. They marveled at our tiny figures and our long, shiny black hair. They praised us for our hardworking ways, ‘That girl never stops until she gets the job done.’ They bragged about us to their neighbors. They bragged about us to their friends. They claimed to like us much more than any of the others. When they were unhappy and had no one else to talk to they told us of their deep, darkest secrets. When their husbands went away on business they asked us to sleep with them in their bedrooms in case they got lonely.

There is a shared sameness between these emigre’ women and their female white counterparts, and at the same time a distance. Each is an accoutrement adorning a difficult existence. We are all like one another. But perhaps not. And then again, yes, exactly alike.

The final chapter is told from the POV of whites left behind to marvel how the Japanese they once saw on a daily basis have now vanished to the camps, leaving behind small homes, decorations, children’s playthings, and remembrances of those once known and now extinguished.

The tone is always intimate. A bit confessional. Mostly a litany of the rejection and discomfort these women feel in this strange new land married to strange new men working strange new jobs so they might survive.

The Buddha in the Attic is both a novel and not a novel. It’s a tableau of impressions from which the reader weaves the story they are as they read it. That’s the book’s charm. That’s its greatness and engagement. The way we watch these women from a distance so we might feel their pain deep within our hearts.

The way we live at a distance from a world we find familiar, and yet hardly know.